The fundamental theorem of finite games

In every finite two-player game of perfect information, either one player has a winning strategy or both players have drawing strategies.

Consider the game of chess—who wins with optimal play? Chess players commonly find a slight advantage for white. Moving first, after all, enables a certain initiative in play and a consequent measure of control over the opening that is simply less available to black, who is often put on the back foot. In light of this advantage, it is customary in friendly games to offer the weaker player white as compensation.

But does white truly have an advantage? And what would it mean exactly to have a “slight” advantage? Does white have an actual winning strategy? That is, is there a way of playing for white, a systematic method of playing in response to every conceivable black counterplay, that will inevitably ensure a white win regardless of how black plays? Or perhaps, contrary to expectations, black has such a winning strategy.

More probably, neither player has a winning strategy. With perfect play, perhaps chess is a draw. Certainly at the top level of play between the best players there are many drawn games—reliably about half of the top-level championship games are drawn. But what does it mean exactly to say that chess is a draw?

Perhaps chess is a draw in the weak sense simply that with optimal play, neither player has a winning strategy—neither player can force a win. That is, every possible white strategy admits counterplay by black that will prevent it from winning; and similarly every possible black strategy admits drawing or defeating counterplay by white.

Or perhaps chess is a draw in the stronger sense that both players positively have drawing strategies, a systematic way of playing that will inevitably lead to a draw or better against any possible counterplay by the opponent.

Are these two ways of formulating what it means to say that chess is draw actually the same? In other words, if neither player has a winning strategy, does it follow that both players have a systematic way of playing that will ensure a draw or better?

Interlude

The fundamental theorem of finite games

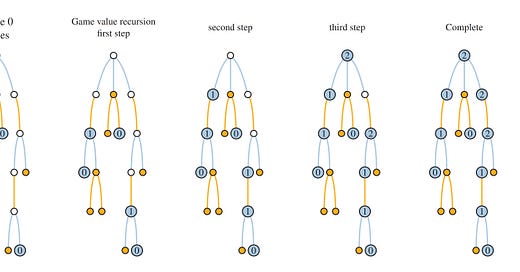

The answer is yes, the two conceptions of what it would mean for chess to be a draw, the weak sense and the strong sense, are equivalent. I find this to be a subtle, nontrivial observation, but one which follows as a consequence from the main result I should like to discuss in this chapter, the fundamental theorem of finite games.

The fundamental theorem of finite games. In every finite two-player game of perfect information, either one of the players has a winning strategy or both players have drawing strategies.

We shall discuss in detail all about this theorem, including five different proofs of it. Let’s get into it.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Infinitely More to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.