The hypergame paradox

A confounding paradox arising in the theory of finite-play games.

Let us agree to define, as may seem very reasonable, that a two-player game of perfect information is a finite-play game, when all plays of the game end with a definite outcome in a finite number of moves. Any instance of the game of Nim, for example, ends with a winner in a finite number of moves, and the same is true for the Gold Coin game, Hex, and so forth. Most all of the games we usually play are finite-play games in this sense—inevitably we bring the games to their conclusion in a finite number of moves.

Perhaps one takes chess and a few other common games as challenging this claim, since we might imagine infinitely long plays of these games. In chess, for example, we can set our knights galloping endlessly around the chessboard, a never-ending horse race with each knight overtaking the other in turn. Nevertheless, the standard tournament rules for chess actually block this kind of arbitrarily long play—the three-fold repetition rule, for example, calls the game a draw after the players repeat the same overall state of the game three times, as must occur in any sufficiently long play, and also the fifty-move rule calls the game a draw whenever there are fifty consecutive moves without any pawn movement or capture, in effect taking those events as a proxy for progress in the game. In some official settings, however, the three-fold repetition rule is specified merely as a player option—a player is entitled to call a draw by repetition but is not obliged to do so when the situation occurs, and this interpretation of the rule would not block infinite play. In other official contexts, however, draw by repetition is compulsory—in many online chess forums the game ends automatically in a draw when the third repetition state occurs. In contrast, the fifty-move rule is usually taken as compulsory when it is in effect and therefore places a definite bound on the longest possible game of chess. So with these established rules, chess becomes a finite-play game. Similar tournament rules apply to draughts and to many other games, specifically with the intention of forcing the game to end in a feasible finite number of moves. Naturally for practicable tournament play in any game one needs a way to ensure that the games will actually end so that the tournament can come to a conclusion.

Hypergame

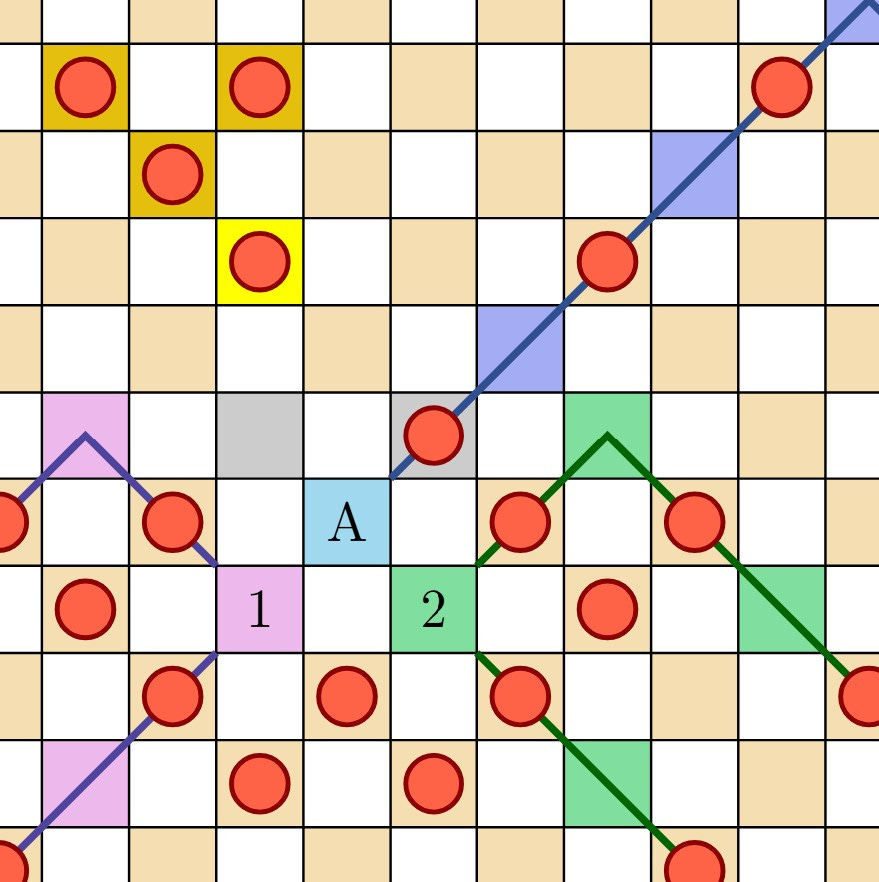

In light of the enormous variety of finite games available to us, let me introduce the game known as hypergame. To play hypergame, the first player selects a particular finite-play game and then play proceeds as in that game. Perhaps the first player selects chess, or an instance of Nim or of Domineering—whichever finite game is selected, the players simply then proceed to play that game; the second player makes what amounts to the first move in the selected game, and game play commences. Whichever player wins the selected game-in-a-game is declared the winner also of the corresponding instance of hypergame.

Plays of hypergame have vastly different game-theoretic natures, since some plays of hypergame are a lot like chess, while other plays are very like Nim or Hex. Of course, hypergame can be a little like any given finite game, if only the first player should choose that game on the first move.

First player strategic advantage

From a strategic point of view, we might observe that the first player in hypergame clearly enjoys an overwhelming strategic advantage, so much so that the game becomes hardly worth playing seriously. After all, the first player could choose the game starting from a hopeless position in chess, where the opponent will be presently checkmated. Or a hopeless tic-tac-toe position. Why not choose a trivial Nim position—two piles, each of height one? Or indeed, why not simply choose the empty Nim position, so that the opposing player loses immediately, before even making a move? This amounts to choosing the “lose immediately” game, which is indeed a finite game, although in truth not one that is very enjoyable to play or exciting to watch. There will never be a professional hypergame league. From this perspective, hypergame would seem to be a rather disappointing game. Why should we consider it at all?

Hypergame is a finite-play game

In order to answer that question, let me first make a certain fundamental observation about hypergame. Specifically, I should like to observe that because the game chosen on the first move of hypergame is required to be a finite-play game, it will conclude in finitely many moves, and consequently, the corresponding play of hypergame itself also will conclude in finitely many moves. In short, all plays of hypergame will come to their outcome in a finite number of moves. Therefore, according to the definition we had provided for what it means to be a game of finite-play, we conclude that the game of hypergame itself is such a game of finite-play.

The hypergame paradox

But now a troubling conundrum arrives into the analysis, like a muddy wild boar appearing suddenly amidst the linens and finery of the garden party. Namely, consider the following instance of the game of hypergame. The first player is called upon to select a particular finite-play game. The mischievous player, thinking not unlike a muddy wild boar, elects for “hypergame.” Precisely because hypergame itself is a finite-play game, according to what we have said, this is a valid first move in hypergame. And so now play in that game commences. The second player should accordingly make the first move in the game that was selected, which therefore calls upon her to select a finite-play game. Catching the mood and equally mischievous, she plays along and selects “hypergame.” And so forth. The players proceed continually to select hypergame again and again:

Hypergame, hypergame, hypergame, hypergame, …

Each next move is a valid legal move, if the previous move was, since whenever a player has chosen to play hypergame, then the next move is to select a finite game, which could be hypergame itself. So according to what we have said, this would be a legitimate play of the game hypergame.

Well, so what? We have found an absurd strange play of this absurd strange game. Do you see the puzzling trouble about it?

Interlude

The puzzling trouble here, the wild-boar nature of the situation, is that this is an infinite play of the game! We found a play of hypergame that does not after all end with a definite outcome in finitely many moves, contrary to our earlier conclusion.

Wait, what? We have found ourselves in explicit contradiction. On the one hand, since hypergame requires that the first player select a finite-play game, which is then played, it seems incontrovertible that all plays of hypergame will end in finitely many moves. But on the other hand, this very fact implies that hypergame itself would be a finite game, and so the first player could select it and we can achieve the infinite play, hypergame, hypergame, hypergame, and so forth, which is not a finite play. So we have argued both that there can be no infinite play of hypergame and also, as a consequence, that there is a specific such infinite play.

What is going on? Let us explore it.

Please enjoy this selection from Infinite Games: Frivolities of the Gods, my new book serialized here with fresh material on games and the logic of games each week.

This week we look into the hypergame paradox, including a discussion of the Russell paradox, the Burali-Forti paradox, game trees, diverse formulations of the hypergame paradox, and much more, culminating in what I call the hypergame theorem.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Infinitely More to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.